Kwanzaa is the Black cultural holiday that you may know of, but not know very much about. Kwanzaa gives Black folx an opportunity for connection with family, community, and their culture. A connection with culture can give us a sense of pride and purpose, and promote our well-being. Kwanzaa is celebrated for a week at the end of the year, and but its principles, which include self-determination, collectivism, and faith in ourselves and each other, are relevant year- round.

I’m going to start with a maybe obvious statement: As a psychologist, I care about mental health. I see it as a critical component of overall well-being. There’s more to mental health than addressing problems, it can and should be about resilience, strength, resourcefulness, and cultivating happiness. As a Black woman, one of the main reasons I became a psychologist is simple: I wanted to do something to make my people, my community, happy. I wanted to uplift us. America (and much of the world at large) invests heavily in oppressing Black folx and communities. One of the most insidious ways has been through stripping us of our culture.

Losing our culture means we lose a sense of who we are, which makes it easier for society to tell us who we are (lazy, inferior, criminal, I won’t go on because we all know). A rediscovery of cultural values may help us to redefine ourselves so that we don’t fall victim to societies’ narratives, and may help us to regain strength, build resilience, and find joy in being who we are. So, during this season of Kwanzaa (sometimes spelled Kwanza), I want to propose that we adopt its principles, not just during its seven days, but throughout the year.

I grew up in a very Pro-Black, Kwanzaa-celebrating family in Oakland. My parents made sure my siblings and I had plenty of Black toys and books (my mom actually wouldn’t let us have White dolls, not because she disliked White people, but because she wanted us to see the beauty in and love our Blackness), we wore our hair natural, we knew our Black history, I read all 800 pages of Roots in the eighth grade, I, my siblings, and most of our cousins went to HBCU’s for college, and at one point, my dad seriously considered legally changing our name to something African (I sucked my teeth so hard…). So, I was pretty grounded in Black culture, and loved it. But I wasn’t into the yearly Kwanzaa celebrations we participated in. My extended family celebrated together, either at a community center, a church, or at a family members’ house. I liked seeing my cousins, some of the food was pretty good, and I even liked the candle-lighting, but overall I didn’t really appreciate Kwanzaa’s purpose, and felt annoyed at the focus on handmade gifts after my parents had already bought me gifts off my Christmas list.

As we got older, we phased Kwanzaa out. Probably because life got busier, and because the adults got tired of the childrens’ complaining. I’m a little ashamed to say that I didn’t return to

Kwanzaa until just a few years ago when I got involved in the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi), which is committed to African-centered psychology and has yearly Kwanzaa celebrations. In refamiliarizing myself with Kwanzaa, I’ve understood it as a way of being rooted in Black culture. Black culture is broad (it’s also not a monolith) and Kwanzaa offers a way to make some key principles accessible and practical. I saw the meaning that Kwanzaa held for my family, and the meaning it could hold for others, if only they understood it.

History and Purpose of Kwanzaa

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor of Africana studies, founded Kwanzaa in 1966. It’s an African American and Pan-African holiday based on African festival traditions, and its name comes from the Swahili phrase matunda ya kwanza, meaning “first fruits”. It was established in Los Angeles following the racially charged Watts Rebellions, but has come to also be celebrated by Black Carribeans and others in the African diaspora as a means of promoting a sense of pride in the Black community and honoring Pan-African history. It lasts for seven days, December

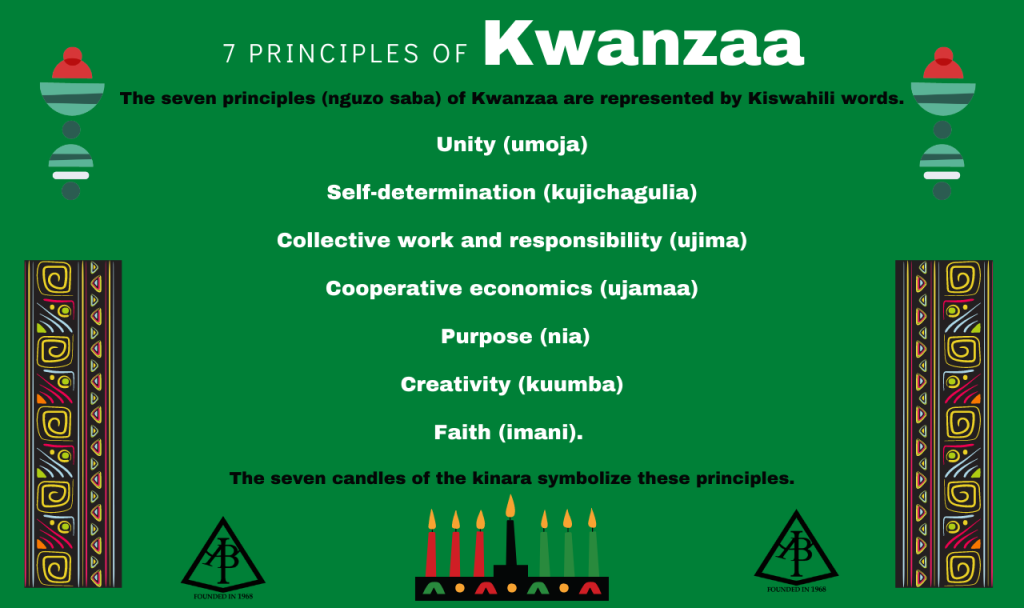

26-January 1st, with a focus on family, community, and culture. In addition to fellowship, culturally significant food, music, poetry, dance, and reflection are a feature. The Nguzu Saba (seven principles) guide the celebrations, with each day devoted to one of the principles. The holiday is meant to “bring a cultural message which speaks to the best of what it means to be African and human in the fullest sense”. I’ll say it again: the best of what it means to beAfrican and human in the fullest sense.So, Kwanzaa is a gift, an opportunity to reflect on take pride in being us. And, the Nguzu Saba promote strength and upliftment, and are relevant year-round, beyond Kwanzaa’s seven days.

The Seven Days of Kwanzaa, and The Nguzu Saba

An important part of Kwanzaa is lighting the kinara, which holds the seven candles that represent the Nguzu Saba. Each night, the celebrants light the candle corresponding to the day and its principle. I’ve listed the principles in the order they’re observed, given a brief explanation and offered some examples of how they might be brought to life (these are just suggestions, by all means, do YOU!)

Day1, Umoja(Unity): “To strive for and maintain unity in the family, community, nation, and race.” Umoja is about joining together- in the family, community, nation, and Black race. This is a nod to the traditional value of collectivism, and the idea that we’re stronger together than we are individually. This can look a lot of different ways, from spending time together to lending each other support in whatever way we can. Umoja is about inclusivity. Black folx come from all over and identify in lots of different ways, but we’re all Black, and our diversity means we have a lot to offer each other, and we should love and respect each other. #ALLBLACKLIVES MATTER.

Day 2, Kujichagulia (Self-determination): To define ourselves, name ourselves, create for ourselves and speak for ourselves.” This is essentially about self-definition, deciding for ourselves who we are, rather than accepting others’ characterizations of us. It’s important to be cognizant of the ways Black folx are portrayed in society, the negative stereotypes are just about everywhere so it’s easy to unknowingly internalize and buy into them. If we know how others are defining us, we can decide whether these definitions fit, resist them if needed, and assert who we really are.

Day 3, Ujima (Collective work and responsibility): “To build and maintain our community together and make our brother’s and sister’s (sic) problems our problems and to solve them together”. Ujima is about recognizing our interconnectedness, knowing that we’re all in this together. It’s to our benefit to help and invest in each other when and where we can. What helps one of us helps all of us, we’re better off if the people around us are better off.

Day 4, Ujamaa (Collective economics): “To build and maintain our own stores, shops and other businesses and to profit from them together.” This is a call to establish, seek out, and support Black-owned businesses. Invest in things that will uplift the Black community. Get involved in the #BuyBlack and #BankBlack movements. And, share the success that we’ve all contributed to.

Day 5, Nia (Purpose): “To make our collective vocation the building and developing of our community in order to restore our people to their traditional greatness.” Each of us should make it our purpose to contribute to our community, and we can reflect on which of our talents and strengths we can use to do that. Nia gives a bit of a nod to collectivism, in that it encourages us to think beyond our individual interests.

Day 6, Kuumba (Creativity): “To do always as much as we can, in the way we can, in order to leave our community more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited it.” Black folx have the unique ability to turn negatives into positives (think about how hymnals, Blues, and rap have roots in storytelling about Black suffering). Our ingenuity has helped us to survive and thrive (for food, African slaves were often given leftovers that Whites rejected, and they managed to transform them into dishes now known as Soul Food). Black creativity comes in many forms, and each of us should get in touch with our own to better our communities, whether that means creating art, or developing solutions to challenges.

Day 7, Imani (Faith): “To believe with all our hearts in our people, our parents, our teachers, our leaders, and the righteousness and victory of our struggle.” Imani is about trusting in our people’s goodness, beauty, intelligence, and talents, and our ability to use them to continue building ourselves up. Sometimes we need reminders of our greatness, so it’s worth reflecting on how far we’ve come and how we’ve done it to help us keep the faith.

It’s likely that you already incorporate some of these principles into your daily life, at least some of the time. And hopefully, some of these resonate with you, and you can see yourself incorporating. And, hopefully you can see the value of these principles, and how living by them can contribute to our individual and collective well-being and happiness.

Habari Gani (traditional Kwanzaa greeting, Swahili for “what’s the news?”)!

—

Written by Dana L. Collins, Ph.D.

NYABPsi Past President

DrDanaCollins.com